I used to talk about “the chain rule” the way people talk about “the cloud”: with confidence, hand-waving, and a quiet hope nobody asks for the exact mechanism.

Then PyTorch did that thing where it calmly returns None for a gradient I swore should exist. No warning. No crash. Just a polite shrug. And suddenly the whole “autograd is automatic” story felt like saying “the printer works automatically” right before you get trapped in a paper-jam feedback loop.

So I sat down and decided to stop treating autograd like a vending machine: insert tensor, receive gradient. Instead, I wanted to see the machinery. The good news: you can. The even better news: once you see it, a lot of the classic training bugs go from “PyTorch is broken” to “oh… I did that.”

This post is a narrative walkthrough of the notebook I wrote while interrogating autograd. It’s Socratic on purpose: short runnable examples, a lot of “wait, why is that happening?”, and a few gotchas that cost real time when you’re training actual models.

How complicated is autograd

The real-world pain isn’t that autograd is complicated. It’s that it’s quietly complicated.

- You build a forward pass, call

.backward(), and your gradients areNone. - Or your gradients are not

None, but they’re inexplicably huge by step 200. - Or your GPU memory usage creeps upward like a horror-movie staircase even though you “aren’t storing anything.”

- Or you implement a custom operation, your math checks out on paper, and

gradchecksays “nope” (with the emotional tone of a failed unit test at 2 AM).

All of those issues are autograd issues—but they’re not “autograd is wrong” issues. They’re “I didn’t understand the graph I built” issues.

The fix, at least for me, was to internalize a mental model:

- Forward builds a directed acyclic graph (DAG).

- Backward traverses that DAG in reverse topological order.

- Gradients are accumulated, not assigned.

That’s it. That’s the whole movie. Everything else is plot twists you cause by changing the graph.

The Technical Deep-Dive

1) Autograd doesn’t know calculus. It records a DAG.

If you’ve ever heard “PyTorch applies the chain rule,” that sentence hides the key detail: PyTorch doesn’t symbolically differentiate your program. It records what you did as you did it.

When you perform tensor ops with requires_grad=True, PyTorch creates a computation graph. Under the hood, each operation adds a node that knows how to send gradients backward—usually as a Jacobian-vector product (JVP) in reverse-mode form.

Here’s the smallest possible graph that still feels like a graph:

x = torch.tensor(3.0, requires_grad=True)

y = x * 2

z = y + 1

print('x:', x, 'requires_grad=', x.requires_grad, 'is_leaf=', x.is_leaf, 'grad_fn=', x.grad_fn)

print('y:', y, 'requires_grad=', y.requires_grad, 'is_leaf=', y.is_leaf, 'grad_fn=', type(y.grad_fn).__name__)

print('z:', z, 'requires_grad=', z.requires_grad, 'is_leaf=', z.is_leaf, 'grad_fn=', type(z.grad_fn).__name__)

A couple things pop immediately:

x.grad_fnisNonebecausexwasn’t produced by an operation. It’s a “leaf” tensor.y.grad_fnandz.grad_fnexist because they’re results of ops (MulBackward0,AddBackward0, etc.).

That grad_fn field is the gateway drug to understanding autograd. It points to an autograd Function node—the backward rule for the op.

Seeing the graph without extra tools

You don’t need graphviz. You don’t need third-party visualizers. You can literally traverse grad_fn.

In the notebook, I wrote a tiny printer that walks grad_fn -> next_functions with a BFS (breadth-first search). It’s not pretty. It is honest.

from collections import deque

def _node_label(fn):

if fn is None:

return 'None'

return type(fn).__name__

def print_autograd_graph(output_tensor, max_nodes=50):

"""Print a simple BFS view of grad_fn -> next_functions."""

root = output_tensor.grad_fn

q = deque([root])

seen = set()

n = 0

while q and n < max_nodes:

fn = q.popleft()

if fn is None or fn in seen:

continue

seen.add(fn)

n += 1

parents = []

for next_fn, _ in getattr(fn, 'next_functions', []):

parents.append(_node_label(next_fn))

q.append(next_fn)

print(f'{_node_label(fn)} -> {parents}')

Then I built a tiny two-input graph and printed it:

a = torch.tensor(2.0, requires_grad=True)

b = torch.tensor(-3.0, requires_grad=True)

c = a * b

d = c + a

print_autograd_graph(d)

What you’ll see is a list of Function nodes, each pointing “backward” to its parents. That’s the DAG. The chain rule is simply the act of traversing this structure in the right order.

Why topological order matters

Backward is basically: “start at the output, propagate gradients to inputs.” But the order matters when nodes depend on others.

In the notebook I also compute a reverse-topological order using a DFS postorder traversal:

def topo_order_from_grad_fn(output_tensor):

root = output_tensor.grad_fn

seen = set()

post = []

def dfs(fn):

if fn is None or fn in seen:

return

seen.add(fn)

for next_fn, _ in getattr(fn, 'next_functions', []):

dfs(next_fn)

post.append(fn)

dfs(root)

return list(reversed(post))

This is one of those “tiny” utilities that feels like trivia until you’re debugging a weird gradient situation. Once you accept that autograd is “just” graph traversal plus local derivatives, the mystique evaporates.

The metaphor I ended up using: forward is writing a recipe; backward is reading it in reverse and multiplying by how much each ingredient mattered.

2) Leaf tensors are where gradients live—and .grad is an accumulator.

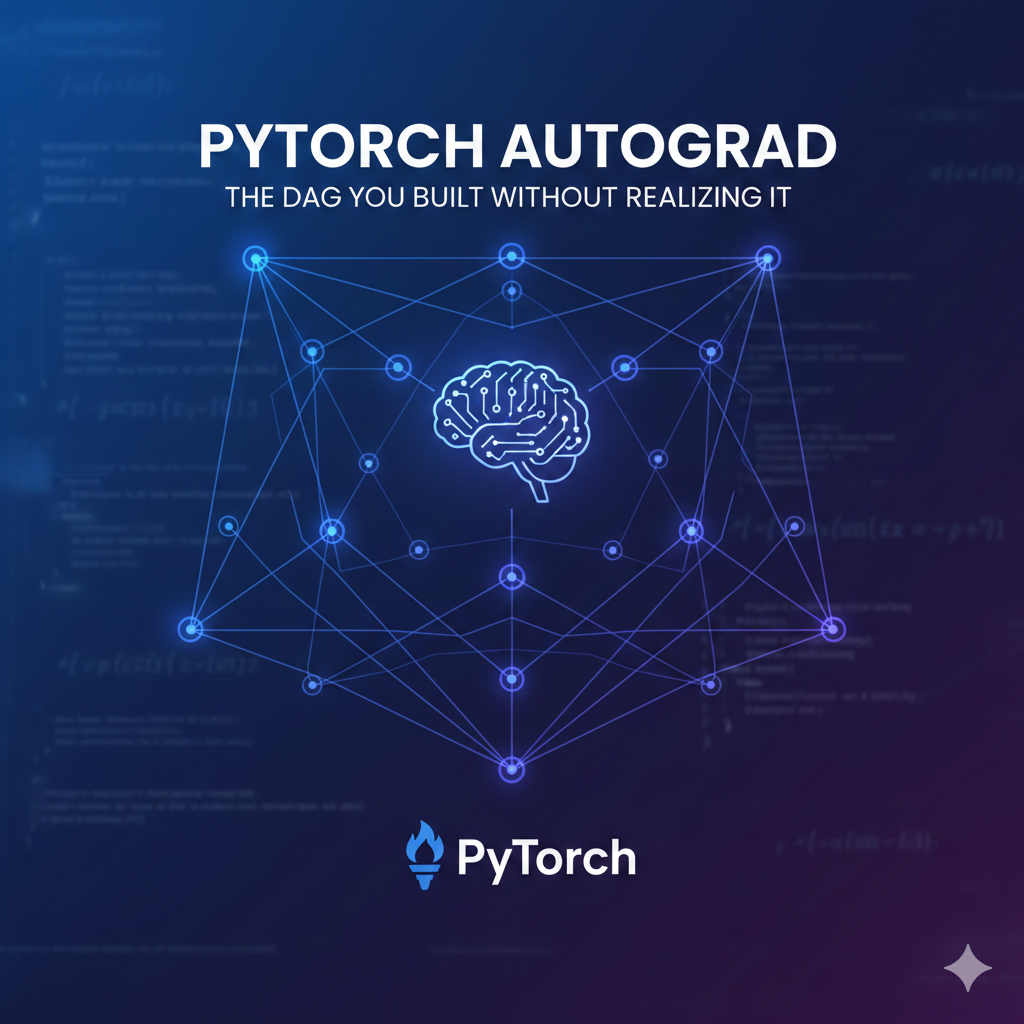

The second autograd surprise (for many people) is that not every tensor gets a .grad. PyTorch mostly stores gradients on leaf tensors (the ones you created and marked requires_grad=True).

This is why the notebook explicitly calls out leaf tensors:

- A leaf tensor is created directly by you, not as the result of an op.

- Leaf tensors with

requires_grad=Trueare the ones that receive gradients in.gradafter backprop. - Intermediate tensors (non-leaf) usually have

grad_fnand don’t keep.gradunless you ask viaretain_grad().

This matters because a lot of “my gradients are missing” bugs boil down to one of these:

- You never set

requires_grad=Trueon the leaf you care about. - You broke the graph using

detach(). - You did the forward under

torch.no_grad().

The notebook lists exactly that, and it’s correct. It’s also kind of funny how often it’s (1) and you just didn’t realize you created your tensor with requires_grad=False.

The chain rule, proven with an embarrassingly tiny example

I love tiny checks because they reduce the problem space. Here’s the notebook’s analytic sanity test:

x = torch.tensor(3.0, requires_grad=True)

f = (x + 1) ** 2 # f(x) = (x+1)^2

f.backward()

print('f:', f.item())

print('df/dx (autograd):', x.grad.item())

print('df/dx (analytic):', (2 * (x.detach() + 1)).item())

assert torch.isclose(x.grad, 2 * (x.detach() + 1))

The derivative is f′(x)=2(x+1). PyTorch produces the same value.

This isn’t interesting because it’s hard. It’s interesting because it establishes trust: the chain rule works when the graph is intact.

The “add” in backprop is not optional

The notebook also stresses something that’s easy to miss if you learned gradients in a single-path calculus course:

- A node can contribute to the loss through multiple downstream paths.

- That means the gradient flowing into that node is a sum of contributions.

That’s why .grad uses accumulation. Which leads directly to the training-loop bug.

3) Gradient accumulation is a feature… until it’s your bug.

If you’ve ever seen a training run “explode” after a few steps, there’s a decent chance you accidentally accumulated gradients.

PyTorch, by default, does this:

.backward()adds into.grad.- It does not overwrite

.grad.

So if you call .backward() twice on two different losses without clearing, you get the sum of gradients.

The notebook demonstrates this in a toy setting:

w = torch.tensor(2.0, requires_grad=True)

def loss_fn(w):

return (w - 5) ** 2

loss1 = loss_fn(w)

loss1.backward()

print('After 1st backward, w.grad =', w.grad.item())

loss2 = loss_fn(w)

loss2.backward()

print('After 2nd backward (no zeroing), w.grad =', w.grad.item())

You’ll watch the gradient double because you computed the same loss twice.

In real training, you don’t compute the same loss twice, but you do compute loss over and over. If you forget to clear gradients each iteration, your .grad becomes “sum of all gradients so far,” which is essentially an unplanned learning-rate multiplier.

It’s like trying to steer a car where the steering wheel keeps turning even after you let go.

The canonical fix pattern

The notebook shows the canonical loop:

w = torch.tensor(2.0, requires_grad=True)

opt = torch.optim.SGD([w], lr=0.1)

for step in range(3):

opt.zero_grad(set_to_none=True)

loss = (w - 5) ** 2

loss.backward()

opt.step()

print(f'step={step} w={w.item():.4f} grad={None if w.grad is None else w.grad.item():.4f} loss={loss.item():.4f}')

A few things worth calling out:

opt.zero_grad(set_to_none=True)is a good default. Setting grads toNone(instead of zeroing to 0) avoids unnecessary memory writes and can help performance. It also makes it easier to detect “this grad was never computed” becauseNoneis a stronger signal than “0.0 but I don’t know why.”- The sequence is consistent: zero, forward, loss, backward, step.

When you want accumulation

The notebook also says this explicitly: sometimes you want gradient accumulation. The most common case is micro-batching when your full batch doesn’t fit.

Conceptually:

- Loop over micro-batches.

- Call

loss.backward()on each micro-batch (accumulating into.grad). - Call

optimizer.step()once. - Clear grads before the next “macro” step.

That’s planned accumulation. The bug is unplanned accumulation.

4) detach() vs torch.no_grad(): same vibe, different physics.

This is the section that made the most things click for me because it’s where you consciously control the graph.

PyTorch gives you two mainstream ways to stop gradients:

tensor.detach()returns a tensor that shares storage but is treated as a constant: it has no gradient history.with torch.no_grad():disables graph recording for operations executed inside the block.

The notebook demonstrates both:

x = torch.tensor(2.0, requires_grad=True)

y_detached = (x * 3).detach()

print('detach: y_detached.requires_grad =', y_detached.requires_grad, 'grad_fn =', y_detached.grad_fn)

with torch.no_grad():

y_nograd = x * 3

print('no_grad: y_nograd.requires_grad =', y_nograd.requires_grad, 'grad_fn =', y_nograd.grad_fn)

# Graph still exists for operations outside no_grad

y = x * 3

print('normal: y.requires_grad =', y.requires_grad, 'grad_fn =', type(y.grad_fn).__name__)

What I like about this example is that it highlights the subtlety:

detach()is local: it breaks the graph at that tensor.no_grad()is contextual: it changes how ops inside the block are recorded.

If you want to stop gradients flowing back from a specific tensor but still keep other graph parts intact, detach() is the scalpel.

If you are doing inference and you want to save memory and speed, no_grad() is the hammer.

The memory leak you accidentally wrote

The notebook also calls out a classic autograd memory bug that doesn’t look like a bug until your GPU is on fire:

Storing tensors that still have a computation history (they have

grad_fn) in a Python list across training steps.

That retains the entire computation graph each time, preventing it from being freed.

The notebook includes a minimal demo:

x = torch.tensor(1.0, requires_grad=True)

history_bad = []

history_good = []

for _ in range(5):

x = x * 1.1 # creates a new node each time

history_bad.append(x)

history_good.append(x.detach())

print('bad entry has grad_fn:', history_bad[-1].grad_fn is not None)

print('good entry has grad_fn:', history_good[-1].grad_fn is not None)

It’s almost comically small, but the mechanism is exactly what happens in real training when you do something like:

losses.append(loss)preds.append(pred)

…without detaching or converting to Python numbers.

If you want to log metrics:

- store

tensor.item()for scalars, - or store

tensor.detach()for tensors, - or compute metrics under

torch.no_grad().

It’s the same pattern: if you don’t need gradients, don’t keep the graph.

5) Custom torch.autograd.Function: your gradient contract is grad_output → grad_input.

Most people can go pretty far without writing a custom autograd Function. But when you need one, you really need one.

The notebook’s explanation is the right mindset:

- In

forward, you compute outputs and optionally save tensors inctx. - In

backward, you receivegrad_output(the gradient of the loss w.r.t. your output), and you must return gradients w.r.t. your inputs.

Or more bluntly:

backwardis not “compute the derivative.”backwardis “compute how the upstream gradient transforms through your local derivative.”

In chain-rule language, if the loss is L and your function is y=f(x):

- You’re given ∂L∂y (

grad_output). - You must return ∂L∂x=∂L∂y⋅∂y∂x.

The notebook uses a cubic function as a clean example:

class MyCustomOp(torch.autograd.Function):

"""Example custom op: cubic f(x) = x^3"""

@staticmethod

def forward(ctx, input):

ctx.save_for_backward(input)

return input ** 3

@staticmethod

def backward(ctx, grad_output):

(input,) = ctx.saved_tensors

grad_input = grad_output * (3 * input ** 2)

return grad_input

Then a smoke test:

x = torch.tensor(2.0, requires_grad=True)

y = MyCustomOp.apply(x)

y.backward()

print('y:', y.item())

print('dy/dx:', x.grad.item(), '(expected 12)')

assert torch.isclose(x.grad, torch.tensor(12.0))

This is one of those moments where writing the code clarifies the concept. The signature of backward forces you to think in terms of upstream gradient multiplication.

Don’t trust yourself: use gradcheck

Even if your math is right, you can get the implementation wrong (dtype issues, shape issues, in-place ops, discontinuities). That’s why gradcheck exists.

The notebook lists the rules, and they’re not negotiable:

- Use

torch.double(float64). - Use small random inputs.

- Avoid nondifferentiable points.

Then it runs gradcheck:

from torch.autograd import gradcheck

x = (torch.randn(3, dtype=torch.double, requires_grad=True) * 0.1)

ok = gradcheck(MyCustomOp.apply, (x,), eps=1e-6, atol=1e-4)

print('gradcheck:', ok)

assert ok

If you’ve never run gradcheck, the first time you do is humbling. It’s basically unit tests for calculus. And yes, it will catch subtle bugs.

The notebook also gives the usual reasons for gradcheck failure:

- float32 precision

- nondeterminism

- in-place ops

- discontinuities

That list is a nice checklist because it points to the kinds of errors that aren’t “wrong derivative” so much as “numerical method can’t verify your derivative.”

6) Building a mini-autograd engine (scalar-only) is the fastest way to stop guessing.

At some point, if you want autograd to feel intuitive, you have to implement it at least once. Not for production. Not for speed. For understanding.

The notebook’s “deep dive project” does exactly that: build a scalar Value type that stores:

data: the scalar valuegrad: the gradient accumulator_prev: parent nodes_op: operation label_backward: a closure that performs local gradient propagation

This is very similar to the classic micrograd-style exercise. The point isn’t novelty. The point is that once you write the topological sort yourself, you stop treating traversal order as a magical property.

Here’s a representative excerpt from the notebook’s implementation:

from dataclasses import dataclass, field

from typing import Callable, Set, Union

Number = Union[float, int]

@dataclass

class Value:

data: float

grad: float = 0.0

_prev: Set['Value'] = field(default_factory=set, repr=False)

_op: str = ''

_backward: Callable[[], None] = field(default=lambda: None, repr=False)

def __post_init__(self):

self.data = float(self.data)

def __add__(self, other: Union['Value', Number]) -> 'Value':

other = other if isinstance(other, Value) else Value(other)

out = Value(self.data + other.data, _prev={self, other}, _op='+')

def _backward():

self.grad += 1.0 * out.grad

other.grad += 1.0 * out.grad

out._backward = _backward

return out

def __mul__(self, other: Union['Value', Number]) -> 'Value':

other = other if isinstance(other, Value) else Value(other)

out = Value(self.data * other.data, _prev={self, other}, _op='*')

def _backward():

self.grad += other.data * out.grad

other.grad += self.data * out.grad

out._backward = _backward

return out

def backward(self) -> None:

topo = []

seen = set()

def build(v: 'Value'):

if v in seen:

return

seen.add(v)

for child in v._prev:

build(child)

topo.append(v)

build(self)

self.grad = 1.0

for v in reversed(topo):

v._backward()

A few things this makes painfully clear:

- You need a topological order.

- You need to traverse it in reverse.

- You must seed the output gradient as 1.0.

- You must accumulate gradients with

+=, not assign.

Once you understand that, PyTorch’s behavior looks less like “autograd did something” and more like “the graph rules did exactly what they always do.”

A concrete example: f(x)=(x+1)2

The notebook builds a scalar graph:

# Build f(x) = (x + 1)^2

x = Value(3.0)

f = (x + 1) ** 2

f.backward()

print('x:', x)

print('Expected df/dx:', 2 * (x.data + 1))

The expected derivative is 2(x+1). When the engine matches it, you’re not just trusting PyTorch—you’re understanding why it’s correct.

Common bugs when writing autograd

The notebook’s recap list is basically the “greatest hits” album of beginner autograd mistakes:

- Forgetting accumulation (

+=) - Wrong traversal order

- Forgetting to seed the output grad

- Mixing up local derivatives (product rule, ReLU masks)

If you’ve ever had a neural net not learn and stared at your optimizer settings like they personally betrayed you, chances are you ran into one of these concepts at a higher level.

The Insight

What I like about PyTorch autograd is that it’s both sophisticated and brutally literal.

It’s sophisticated because it supports a huge space of tensor ops, efficient reverse-mode autodiff, saved tensors, custom ops, and more. But it’s literal because it does exactly what your program tells it:

- If you break the graph (

detach()), it won’t invent gradients. - If you disable recording (

no_grad()), it won’t record anyway. - If you backprop twice without clearing

.grad, it will happily add them. - If you keep references to tensors with

grad_fn, it will keep the graph alive—because you asked it to, whether you meant to or not.

Industry-wise, there are other autodiff styles and ecosystems—JAX with functional transforms, TensorFlow graphs (eager + compiled), and the broader world of compiler-based autodiff. A lot of the “future” feels like pushing more computation into compilation and graph capture for speed.

But even if the tooling gets fancier, this still matters. Because the bugs don’t come from “autodiff is hard.” The bugs come from “I didn’t realize I built that graph.”

My practical takeaways after writing the notebook:

- When gradients are

None, first checkis_leaf,requires_grad, and whether you ran under no-grad. - Treat

.gradlike a sum accumulator; make clearing explicit. - Use

detach()for logging and caching, and useno_grad()for inference. - If you write a custom op,

gradcheckis your friend (and occasionally your judge). - If you’re still unsure, implement a toy scalar autograd once. You’ll stop guessing.

Autograd isn’t magic. It’s a DAG. And the moment you start thinking “what graph did I just build?”, you stop fighting PyTorch and start using it.