Before We Touch Tensors: What a Neural Network Is (and What It’s Made Of)

If you’re totally new to neural networks, here’s the awkward truth: most tutorials start inside the machinery. They’ll show you a Linear layer, a ReLU, maybe an optimizer, and then say “train for 10 epochs.” That’s like teaching someone to drive by handing them a wrench and saying “the engine is over there.”

So before this blog drops you into shapes, broadcasting, and autograd graphs (the stuff you actually need to learn PyTorch), I want to lay down a beginner-friendly map of what a neural network is, what components it usually has, and -most importantly -why those components exist?

You don’t need calculus for this section. You mostly need two mental models:

- A neural network is a function you’re trying to learn from data.

- Training is choosing parameters so that function behaves the way you want.

That’s it. Everything else—layers, activations, losses, gradients, optimizers—is just plumbing that makes those two ideas practical.

A geometry mental model

If the words “layer,” “activation,” and “backprop” feel abstract, try this: pretend your data points live in a geometric space.

- Each input example is a point.

- Each feature is a coordinate axis.

- A batch is just a stack of points.

So if your input has shape (B, D), you can read that as:

Bpoints- in a

D-dimensional space

Now the goal of a classifier is basically geometric: separate points of different classes. In 2D, that might mean drawing a line. In 3D, a plane. In D dimensions, a hyperplane.

The problem is: a single hyperplane often can’t separate real data. So neural networks do something clever:

They repeatedly transform the space so that the classes become easier to separate.

That’s what “learning features” really means: the network is learning a sequence of transformations that re-express your points in a friendlier coordinate system.

1) The Core Idea: A Neural Network Is a Big Function With Knobs

At the highest level, a neural network is a function fθ(x).

- x is your input (an image, a sentence, a tabular row).

- (theta) is a pile of parameters: weights and biases.

- fθ(x) produces an output (a class label, a score, a probability, a prediction).

The “neural” part is mostly branding. The engineering part is: we pick a flexible function family, and then we fit it to data by adjusting .

Why do we need a flexible function? Because most real relationships between inputs and outputs aren’t linear. If they were, linear regression would have eaten the world and we’d all be done.

2) Layers: How We Build a Complicated Function From Simple Parts

Instead of writing one gigantic equation, we stack simple transformations.

The most common building block is an affine transform (a linear layer). In geometry terms, an affine transform is:

- a linear transformation (rotate / scale / shear / project)

- plus a translation (shift)

That’s exactly what a PyTorch linear layer computes:

y=xWT+b

Reasoning:

- Matrix multiplication is expressive and efficient. It mixes information across features.

- The bias term b matters. Without it, your function is forced through the origin, which is an unnecessary restriction in most tasks.

- It’s differentiable. That’s key because training relies on gradients.

A concrete 2D example: “weights” are a transformation matrix

Let’s pretend each input point has just two features (so you can visualize it). A linear layer with in_features=2 and out_features=2 is literally a 2×2 matrix plus a 2D shift:

import torch

# Four points on the axes in 2D

x = torch.tensor([

[ 1.0, 0.0],

[ 0.0, 1.0],

[-1.0, 0.0],

[ 0.0, -1.0],

]) # shape: (B=4, D=2)

# Think of W as “how we stretch/rotate space”

W = torch.tensor([

[2.0, 0.0],

[0.0, 0.5],

]) # shape: (out=2, in=2)

# Think of b as “how we shift space”

b = torch.tensor([1.0, -1.0]) # shape: (out=2,)

y = x @ W.T + b

print('x shape:', x.shape)

print('W shape:', W.shape)

print('b shape:', b.shape)

print('y shape:', y.shape)

print(y)

Geometric interpretation:

x @ W.Tscales the x-axis by 2 and the y-axis by 0.5 (a squish/stretch).+ bshifts every transformed point by(1, -1).

That’s why shape discipline matters so much: the whole “layer” is just matrix math. If your tensors aren’t shaped the way you think, you’re not doing the transform you think you’re doing.

But here’s the catch: stacking linear layers without anything in between doesn’t help. Two linear transforms composed are still a linear transform. In other words:

(xW1T+b1)W2T+b2=x(W2W1)T+(b1W2T+b2)

That’s still “linear + bias.” So if neural nets were only linear layers, they’d be fancy linear regression.

Geometrically: linear layers can only ever take your space and apply an affine transform. They can’t “curve” anything. If your classes are arranged like concentric circles, no amount of rotating and scaling will separate them with a single straight line.

3) Activations: The Nonlinearity That Makes the Network Worth Having

To learn complicated patterns, you need nonlinear behavior.

That’s what activations do. They’re simple functions applied elementwise (usually) between linear layers.

Common ones:

- ReLU: ReLU(x)=max(0,x)

- Sigmoid: σ(x)=11+e−x

- Tanh: tanh(x)=ex−e−xex+e−x

Reasoning:

- Activations create a function that can bend and fold space, not just scale and rotate it.

- ReLU is popular because it’s computationally cheap and tends to train well.

- Sigmoid/Tanh are still useful (especially in gating mechanisms), but they can saturate and make gradients tiny.

Geometry intuition: activations “warp” space

Here’s a beginner-friendly way to think about it:

- A linear layer changes your coordinate system (affine transform).

- An activation changes the shape of the space (nonlinear warp).

ReLU is the easiest to picture. In 1D, it clamps negatives to 0. In higher dimensions, it clamps each coordinate independently. That means it “folds” space along the coordinate hyperplanes. What’s wild is that this fold is exactly what allows a network to create complex decision boundaries.

If you stack Linear → ReLU → Linear, you get a function that is piecewise linear: it’s made of linear regions stitched together at the ReLU “kinks.” Those kinks are where the model gains expressiveness.

This also explains a common beginner confusion: a network with ReLU can represent a curved-looking decision boundary, even though each piece is linear. It’s a polygonal approximation built out of many straight segments.

This is where the “shape discipline” starts to matter in practice: activations are usually elementwise, so they expect the tensor shapes to already make sense. When shapes are wrong, activations won’t necessarily crash—they’ll just compute nonsense quickly.

4) The Forward Pass: A Pipeline of Tensor Operations

When you run a network, you’re doing a forward pass: compute outputs from inputs.

Even a simple MLP (multi-layer perceptron) looks like:

- Linear: h1=xW1T+b1

- Activation: a1=ReLU(h1)

- Linear: h2=a1W2T+b2

- Output transform: maybe logits, maybe probabilities

In PyTorch, this becomes a chain of tensor ops. That’s why the rest of this blog (tensor ops, broadcasting rules, reshape/view pitfalls) is not “intro fluff.” It’s literally the substrate your model runs on.

Geometrically, every forward pass is “move the points through a sequence of coordinate changes and warps.” If you keep that picture in your head, the components feel less random.

5) Loss Functions: Turning “Wrong” Into a Number You Can Minimize

Training needs a measurable notion of “badness.” That’s the loss.

You pick a loss L(y^,y) that compares the model’s prediction to the true target .

Common patterns:

- Classification: cross-entropy loss (works with logits)

- Regression: mean squared error (MSE)

Reasoning:

- The loss is how you translate the problem into an optimization objective.

- A good loss is differentiable (or at least sub-differentiable) so gradients exist.

- The loss is scalar (usually). Autograd needs a scalar “top” to backprop from.

If you’re wondering why people obsess over “logits vs probabilities,” it’s because losses are picky about what they expect. Feeding a probability into a loss that expects logits can still run but behave badly numerically.

Geometry translation: the loss is how you tell the model what “close” means. In classification, you’re not measuring Euclidean distance between points -you’re measuring how confidently the model separates them. In regression, you often are measuring distance (e.g., squared error).

6) Backpropagation: How the Network Figures Out Which Knobs to Turn

Once you have a scalar loss, you want to know how to change parameters to make it smaller.

That means computing gradients: ∇θL.

Reasoning:

- A gradient tells you the direction of steepest increase.

- So moving opposite the gradient decreases the loss (locally).

Backpropagation is just an efficient way to compute these gradients using the chain rule through the computation graph.

Geometry translation: gradients tell you which small tweak to θ would move your decision boundary in a helpful direction. If your boundary is cutting through a cluster of points, the gradients are effectively telling you “rotate/shift/warp the space so those points land on the right side.”

The rest of this blog’s autograd section (including visualizing grad_fn and understanding leaf tensors) exists because gradient bugs are often graph bugs:

- you detached something unintentionally

- you broke the graph with in-place ops

- you expected

.gradon an intermediate tensor (non-leaf)

7) Optimizers: The Rule That Updates Parameters

Gradients alone don’t update weights. You need an update rule.

The simplest is SGD (stochastic gradient descent):

θ←θ−η∇θL

where η is the learning rate.

Common alternatives:

- Momentum (SGD + velocity)

- Adam (adaptive learning rates + momentum-like behavior)

Reasoning:

- Different optimizers trade off stability, speed, and sensitivity to hyperparameters.

- But they all rely on the same input: gradients.

In practice, a shocking amount of training “mystery” is just gradients being wrong (or silently accumulating) and optimizers faithfully applying a bad update.

8) Regularization: Preventing the Network From Memorizing

Neural nets are flexible enough to memorize noise. Regularization is how you discourage that.

Common components:

- Weight decay (L2 regularization): penalizes large weights

- Dropout: randomly zeros activations during training

- Data augmentation: changes inputs so the model can’t memorize exact examples

- Early stopping: stop when validation loss stops improving

Reasoning:

- You want the model to generalize beyond training data.

- Regularization adds constraints or noise that make memorization harder.

This connects back to “boring tensor hygiene,” because regularization often involves operations like masking (dropout) or adding noise—both of which are shape-sensitive. Broadcasting can absolutely sabotage regularization if you apply a mask with the wrong shape and it expands in a way you didn’t intend.

9) Batch Dimension: Why Everything Has a Leading Axis (and Why Broadcasting Loves to Confuse It)

Beginners often think in single examples. Training happens in batches.

So most tensors get a leading batch dimension:

- A single input vector might be

(D,). - A batch of them becomes

(B, D).

Reasoning:

- Batching makes computation efficient (vectorized ops).

- Batching stabilizes gradient estimates.

But it also introduces the single most common source of “it runs but it’s wrong”: applying something shaped like (D,) to something shaped like (B, D) and accidentally getting (B, B) or (B, D) for the wrong reason.

This is why broadcasting rules are both a gift and a trap. They’re deterministic, but they don’t know your intent.

If you like the geometry framing: a batch is just many points. Broadcasting bugs often happen when you accidentally apply a per-point offset as if it were a “compare every point to every other point” operation (turning (B, 1) + (B,) into (B, B)), which is a totally valid operation… just not the one you meant.

10) The Minimal “Neural Network Components” Checklist

If you want a quick beginner inventory of what most neural networks include, here’s the practical checklist:

- Parameters: weights and biases (the knobs)

- Layers: linear/conv/attention blocks (how you transform inputs)

- Nonlinearities: ReLU/sigmoid/tanh (what makes the model expressive)

- Loss: scalar objective that measures wrongness

- Optimizer: update rule that applies gradients

- Regularization: techniques that fight memorization

- Training loop: forward → loss → backward → step → zero grads

And here’s the reasoning glue that holds it together:

- Layers define a function family.

- Activations make it nonlinear.

- Loss provides a training signal.

- Backprop computes gradients of that signal.

- Optimizers apply those gradients.

- Regularization prevents overfitting.

If that mental model feels clear, you’re ready for the “real” Day 1 pain: tensor shapes, broadcasting, and the autograd graph that powers the whole thing.

Lets understand basics of pytorch

This week I had one of those debugging sessions that makes you question your career choices.

Everything “worked.” The code ran. The GPU fans spun up like a jet engine. The loss even went down. And yet the model’s outputs were nonsense—confident nonsense, the worst kind. It took me longer than I’d like to admit to realize the culprit wasn’t some exotic optimizer issue or a cursed learning-rate schedule.

It was broadcasting.

Not the “it crashed with a helpful error message” kind. The other kind: silent broadcasting that technically follows the rules while quietly turning your intended vector operation into a full matrix operation. In other words: PyTorch did exactly what I asked, not what I meant.

So I made a notebook that’s basically a day-one survival kit:

- A tensor ops cheat sheet that’s not just “here are methods,” but “here are methods with verification asserts.”

- Broadcasting rules + pitfalls with the kind of examples that are unreasonably realistic.

- A tiny autograd inspection tool that prints a readable dependency graph starting from

result.grad_fn, no Graphviz required.

If you’ve ever stared at grad is None like it personally betrayed you, welcome.

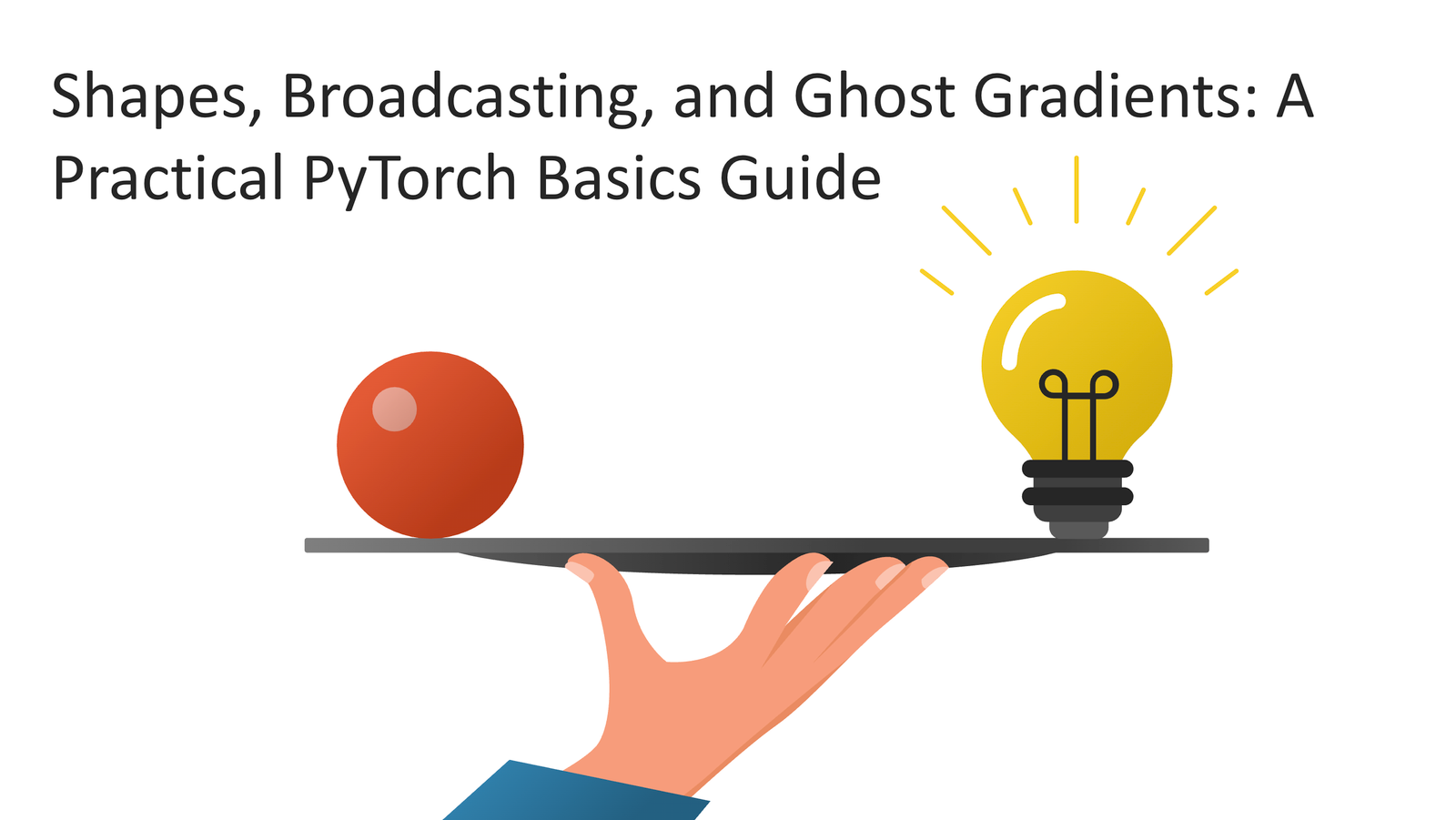

Common bugs

Most deep learning bugs don’t show up as dramatic crashes. The ones that steal your life come in two flavors:

-

Shape bugs: Your tensors don’t have the shapes you think they do.

-

Gradient bugs (or “ghost gradients”): Your tensors have gradients you didn’t expect, or don’t have gradients you desperately need.

And the reason these hurt is not that they’re complicated. It’s that they’re distributed. The mistake happens in one cell/file, and you feel the consequences twenty layers later in a loss curve that looks like a sad seismograph.

Here’s the kind of developer experience I’m trying to prevent:

- You do a reshape.

- Later,

matmulcomplains. - You “fix” it with a

view. - Now something is non-contiguous.

- You add

.contiguous(). - The code runs.

- The model trains.

- The model learns garbage.

The notebook approach I’m advocating is boring in the best way:

- Print shapes and dtypes.

- Write down what you expect.

- Assert it.

- When gradients look haunted, inspect the graph.

Let’s walk through the core ideas, using real code straight from the notebook.

The Technical Deep-Dive

1) Treat shapes like types (and enforce them)

If you only adopt one habit, let it be this: make shape expectations executable. That turns “I think this is (B, D)” into “this must be (B, D) or the notebook stops right here.”

The notebook starts by defining a couple tiny helpers:

def expect_shape(t, shape):

actual = tuple(t.shape)

assert actual == tuple(shape), f'expected shape {shape}, got {actual}'

def expect_close(a, b, *, atol=1e-6, rtol=1e-6):

if isinstance(a, torch.Tensor):

a = a.detach().cpu()

if isinstance(b, torch.Tensor):

b = b.detach().cpu()

torch.testing.assert_close(a, b, atol=atol, rtol=rtol)

def shape_str(t):

return f'shape={tuple(t.shape)}, dtype={t.dtype}, device={t.device}'

This is not glamorous, but it changes the whole experience:

- You don’t have to “remember” what shape something is.

- You don’t have to keep the mental stack of shapes in your head.

- You don’t have to wait until the loss becomes weird.

You get quick failures, close to the root cause.

If you’re coming from typed languages, this is the closest equivalent to “shape is a type parameter” that you can realistically maintain in a notebook.

2) Start with tensor creation, but verify what you created

PyTorch tensor creation is “easy” until you realize there are five ways to create something that looks the same but differs in dtype, device, or grad tracking.

The notebook’s creation cell intentionally prints metadata and then asserts shapes:

# Tensor creation

t1 = torch.tensor([[1.0, 2.0], [3.0, 4.0]])

t2 = torch.zeros((2, 3), dtype=torch.float32)

t3 = torch.ones((1, 4), dtype=torch.float32)

t4 = torch.arange(0, 6).reshape(2, 3)

t5 = torch.linspace(0.0, 1.0, steps=5)

t6 = torch.randn((3, 2))

print('t1', shape_str(t1), '', t1)

print('t2', shape_str(t2))

print('t3', shape_str(t3))

print('t4', shape_str(t4), '', t4)

print('t5', shape_str(t5), '', t5)

print('t6', shape_str(t6))

expect_shape(t1, (2, 2))

expect_shape(t2, (2, 3))

expect_shape(t3, (1, 4))

expect_shape(t4, (2, 3))

expect_shape(t5, (5,))

expect_shape(t6, (3, 2))

assert t1.dtype == torch.float32

assert t2.dtype == torch.float32

Two underappreciated lessons here:

arangedefaults to integer dtype (oftenint64). That’s fine for indexing, not fine for floating-point math unless you cast.- Printing the tensor is not enough. You want the shape, dtype, and device on every “important” tensor.

This is also where I like to insert the first opinion:

If you aren’t printing dtype/device early, you’re outsourcing your debugging to future-you.

3) Indexing and slicing: predictable operations, unpredictable mistakes

Indexing and slicing are conceptually straightforward, which is why the mistakes are extra embarrassing. The notebook includes:

- integer indexing

- slices

- ellipsis

- boolean masks

- fancy indexing

Here’s the core cell:

x = torch.arange(0, 12).reshape(3, 4)

print('x', x)

# integer indexing

a = x[0, 0]

b = x[2] # row

c = x[:, 1] # column

# slicing

d = x[1:, 2:]

e = x[..., -1] # last column using ellipsis

# boolean mask

mask = x % 2 == 0

f = x[mask]

# fancy indexing

rows = torch.tensor([0, 2])

cols = torch.tensor([1, 3])

g = x[rows[:, None], cols[None, :]]

print('a', a.item())

print('b', b)

print('c', c)

print('d', d)

print('e', e)

print('f', f)

print('g', g)

assert a.item() == 0

expect_shape(b, (4,))

expect_shape(c, (3,))

expect_shape(d, (2, 2))

expect_shape(e, (3,))

assert f.numel() == 6

expect_shape(g, (2, 2))

expect_close(g, torch.tensor([[1, 3], [9, 11]]))

A few practical takeaways:

x[2]dropping a dimension is expected, but it’s also how you accidentally turn(B, T, D)into(T, D)and then wonder why batching exploded.- Boolean masks flatten selection results in a way that can surprise you (

fbecomes 1D). If you expected a 2D structure, you probably wantedmasked_fillorwhere. - Fancy indexing like

x[rows[:, None], cols[None, :]]is powerful and also easy to abuse. I include it because it’s common in “select these batch elements and these feature indices” situations.

Here’s my mental model: indexing is like a chainsaw. It does exactly what it does. It is not responsible for your fingers.

4) Reshaping: where “it works” and “it’s correct” diverge

Reshape operations are deceptively easy to sprinkle around until your code “works” but represents a different computation.

The notebook’s reshape cell does a few key things:

flatten()andreshape()unsqueeze()/squeeze()transpose()- an invalid reshape that is expected to fail

y = torch.arange(0, 24).reshape(2, 3, 4)

print('y', shape_str(y))

y_flat = y.flatten()

y_2d = y.reshape(6, 4)

y_unsq = y_2d.unsqueeze(0)

y_sq = y_unsq.squeeze(0)

y_t = y_2d.transpose(0, 1)

expect_shape(y_flat, (24,))

expect_shape(y_2d, (6, 4))

expect_shape(y_unsq, (1, 6, 4))

expect_shape(y_sq, (6, 4))

expect_shape(y_t, (4, 6))

# Invalid reshape example

try:

_ = y.reshape(5, 5)

raise AssertionError('Expected invalid reshape to fail')

except RuntimeError as e:

print('Invalid reshape failed as expected:', str(e).splitlines()[0])

This is the first place where “assertion as pedagogy” shines. You don’t just claim an invalid reshape fails—you prove it, and you prove it in a way that will keep proving it six months from now.

5) view() vs reshape(): a non-contiguity trap that bites everyone

This sounds fine until you transpose.

Transpose (and some other operations) produce a non-contiguous tensor view. view() can only reinterpret a contiguous block of memory, so it may fail.

The notebook makes the failure explicit:

m = torch.arange(0, 12).reshape(3, 4)

mt = m.transpose(0, 1) # non-contiguous view

print('mt is contiguous?', mt.is_contiguous())

try:

_ = mt.view(12)

raise AssertionError('Expected view on non-contiguous tensor to fail')

except RuntimeError as e:

print('view failed as expected:', str(e).splitlines()[0])

ok1 = mt.reshape(12)

ok2 = mt.contiguous().view(12)

expect_close(ok1, ok2)

expect_shape(ok1, (12,))

A clean metaphor:

view()is “same underlying bytes, new shape.”reshape()is “try a view, and if you can’t, make a copy and give me the shape anyway.”

So reshape() is safer for correctness, and view() is stricter about memory layout.

If you ever wondered why your code works on one tensor but fails after a transpose or permute, this is usually the reason.

6) Broadcasting rules: deterministic, but indifferent to your intent

Now we get to the bug that started this whole thing.

The notebook states broadcasting rules plainly:

- Align shapes from the right.

- Dimensions match if they’re equal or one of them is 1.

- Otherwise: error.

It also includes a small table and then drills with “predict the output shape” exercises. The exercises matter because you can’t debug broadcasting if you can’t predict it.

Here’s an example from the exercise cell:

a = torch.zeros(3, 4)

b = torch.zeros(4)

expect_shape(a + b, (3, 4))

a = torch.zeros(3, 1)

b = torch.zeros(3)

expect_shape(a + b, (3, 3)) # common pitfall

That second one is the trap: (3, 1) + (3,) becomes (3, 3) because (3,) behaves like (1, 3) during alignment, and then both sides expand.

This is mathematically consistent. It’s also frequently not what you meant.

Incompatible shapes: when PyTorch does you a favor

Sometimes you do get an error, and it’s a gift.

a = torch.zeros(2, 3)

b = torch.zeros(3, 2)

try:

_ = a + b

raise AssertionError('Expected incompatible broadcast to fail')

except RuntimeError as e:

msg = str(e).splitlines()[0]

print('Broadcasting error (expected):', msg)

print('Translation: last dimensions (3) and (2) dont match, and neither is 1.')

When broadcasting errors appear, I recommend translating them into “shape algebra” immediately. Your future self will start to recognize patterns.

The silent bug: when broadcasting creates a matrix you didn’t ask for

Here’s the star of the show. The notebook demonstrates a silent broadcasting pitfall:

batch = 4

scores = torch.arange(batch).float().unsqueeze(1) # (B,1)

bias = torch.arange(batch).float() # (B,)

bad = scores + bias

good = scores + bias.unsqueeze(1)

print('scores', tuple(scores.shape), 'bias', tuple(bias.shape))

print('bad shape', tuple(bad.shape), '(this is the silent bug)')

print('good shape', tuple(good.shape))

expect_shape(bad, (batch, batch))

expect_shape(good, (batch, 1))

Why does bad become (B, B)?

scoresis(B, 1).biasis(B,), which aligns as(1, B).(B, 1) + (1, B)broadcasts to(B, B).

That’s the kicker: the rules allow it.

And that’s why the blog post is aggressively opinionated about one thing:

Broadcasting is not evil. Implicit broadcasting is.

If you intend a (B, 1) bias, make it (B, 1). Use unsqueeze. Then assert. Don’t let PyTorch guess.

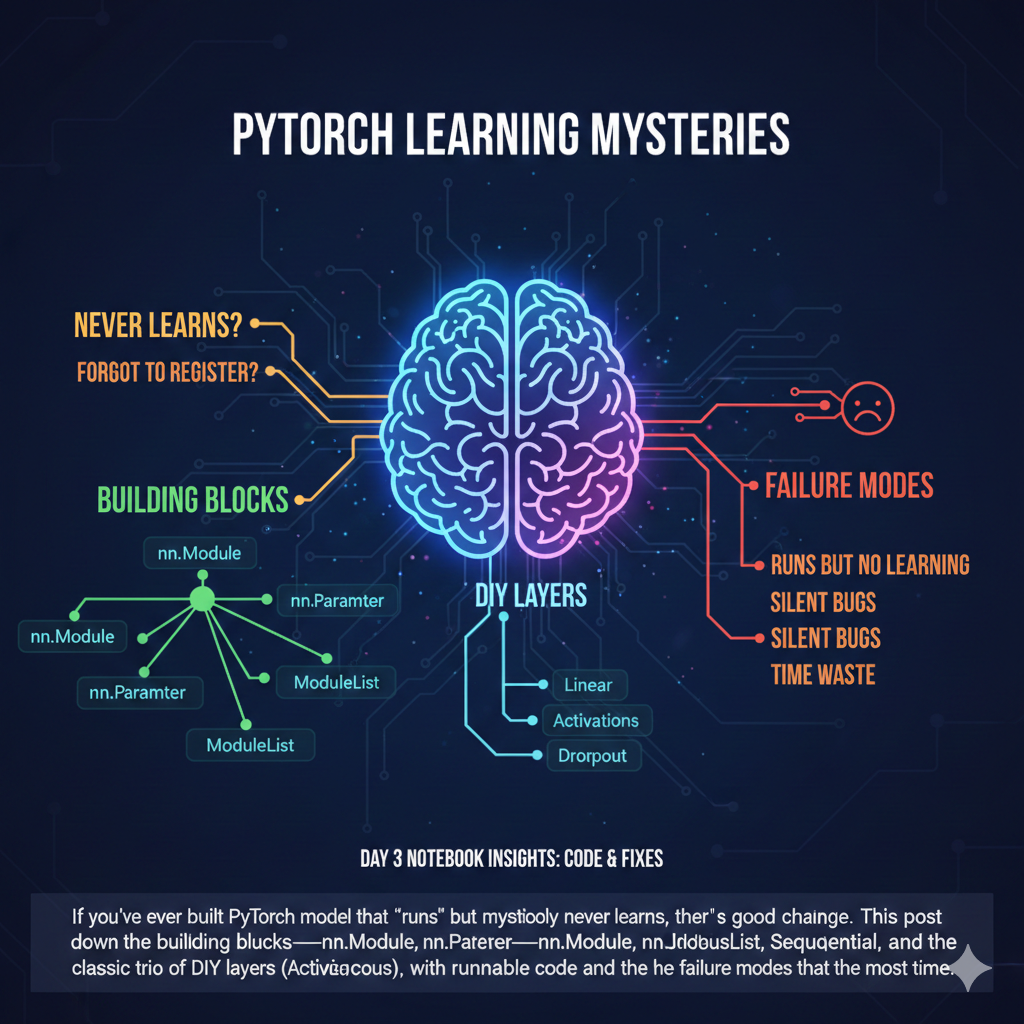

7) Computational graphs and “ghost gradients”

Once shapes are under control, the next debugging tax is gradients.

The notebook introduces autograd metadata:

requires_gradgrad_fnis_leaf.gradbehavior

A small example makes the key distinction:

x = torch.randn(3, requires_grad=True)

w = torch.randn(3, requires_grad=True)

b = torch.randn((), requires_grad=True)

y = (x * w).sum() + b

print('x.requires_grad:', x.requires_grad, 'x.is_leaf:', x.is_leaf, 'x.grad_fn:', x.grad_fn)

print('y.requires_grad:', y.requires_grad, 'y.is_leaf:', y.is_leaf, 'y.grad_fn:', type(y.grad_fn).__name__)

assert x.is_leaf

assert w.is_leaf

assert b.is_leaf

assert (not y.is_leaf)

assert y.grad_fn is not None

Interpretation:

x,w,bare leaf tensors because they were created directly by you andrequires_grad=True.yis not a leaf tensor because it was created by operations.y.grad_fnpoints to the function that produced it.

Now the “ghost gradient” part:

- Leaf tensors accumulate gradients in

.gradafterbackward(). - Non-leaf tensors do not store

.gradby default.

That’s why this is normal:

x = torch.tensor([1.0, 2.0, 3.0], requires_grad=True)

z = x * 2

loss = z.sum()

loss.backward()

assert x.grad is not None

assert z.grad is None

…and if you want z.grad, you have to ask:

x = torch.tensor([1.0, 2.0, 3.0], requires_grad=True)

z = x * 2

z.retain_grad()

loss = z.sum()

loss.backward()

assert z.grad is not None

This is a big deal for debugging because people often try to inspect gradients “in the middle” of the graph and then conclude something is broken. Most of the time, nothing is broken—you just didn’t retain it.

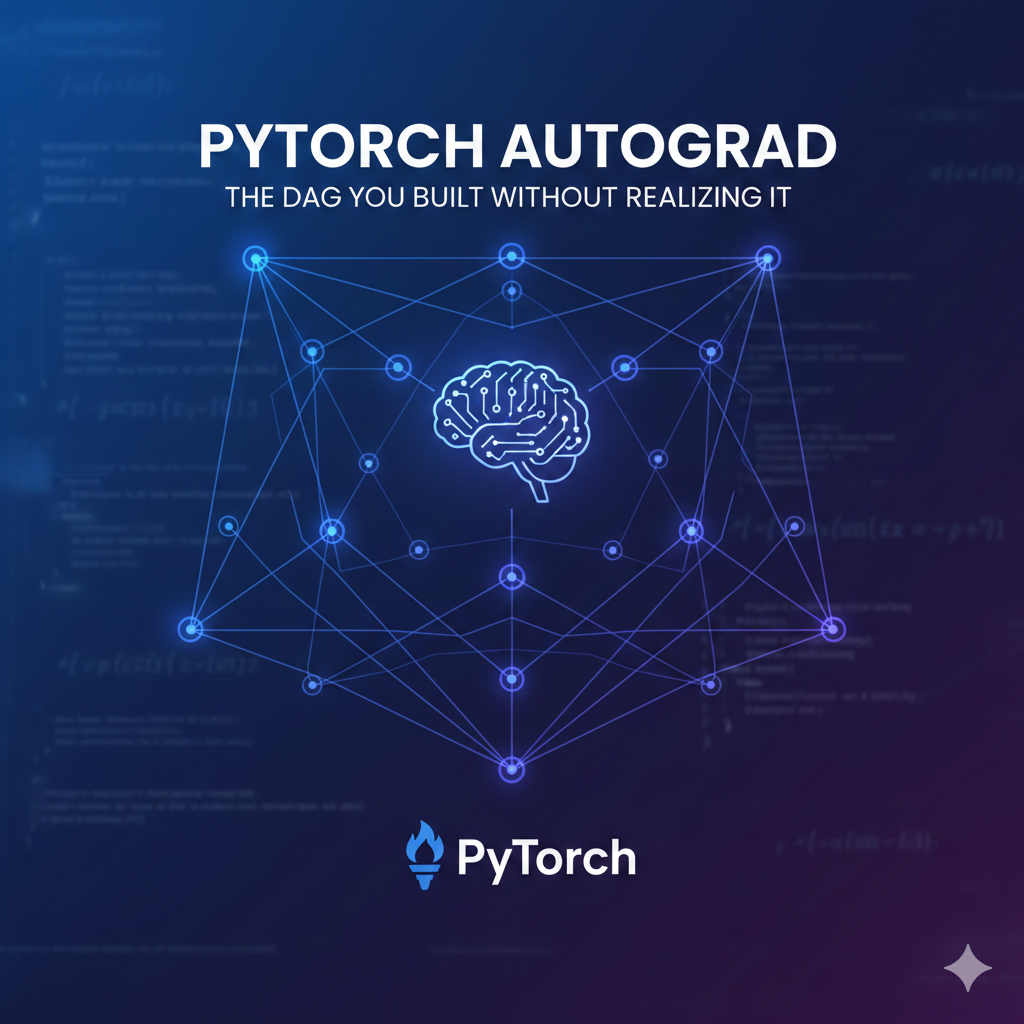

8) A tiny autograd graph visualizer (no Graphviz required)

At this point, you know what grad_fn is, but it still feels abstract. So the notebook implements a small visualizer.

The guiding idea:

- Start from

result.grad_fn. - Recursively traverse

fn.next_functions. - Track

visitedso shared subgraphs don’t loop forever. - Support a

max_depthto keep output readable. - Special-case

AccumulateGradnodes because they link to a leaf tensor viafn.variable.

Here’s the core implementation from the notebook:

def topo_sort_grad_fns(root_grad_fn):

order = []

visited = set()

def dfs(fn):

if fn is None or fn in visited:

return

visited.add(fn)

nexts = getattr(fn, 'next_functions', None)

if nexts is not None:

for nxt, _idx in nexts:

dfs(nxt)

order.append(fn)

dfs(root_grad_fn)

return order

def visualize_autograd_graph(result: torch.Tensor, *, max_depth: int = 50):

if not isinstance(result, torch.Tensor):

return ['(not a tensor)']

if result.grad_fn is None:

return [

'No autograd graph: result.grad_fn is None.',

f'requires_grad={result.requires_grad} (if False, nothing is tracked).',

]

lines = []

visited = set()

def label_fn(fn):

return type(fn).__name__

def recurse(fn, indent, depth):

if fn is None:

lines.append(f'{indent}- ')

return

if depth > max_depth:

lines.append(f'{indent}- {label_fn(fn)} (max_depth reached)')

return

if fn in visited:

lines.append(f'{indent}- {label_fn(fn)} (seen)')

return

visited.add(fn)

# AccumulateGrad nodes have a .variable pointing to the leaf tensor

if hasattr(fn, 'variable'):

v = fn.variable

leaf_meta = f'shape={tuple(v.shape)}, dtype={v.dtype}, requires_grad={v.requires_grad}'

lines.append(f"{indent}- {label_fn(fn)} [{leaf_meta}]")

else:

lines.append(f'{indent}- {label_fn(fn)}')

nexts = getattr(fn, 'next_functions', None)

if nexts is None:

return

for nxt, _idx in nexts:

recurse(nxt, indent + ' ', depth + 1)

lines.append('Autograd dependency graph (functions):')

recurse(result.grad_fn, indent='', depth=0)

return lines

A few notes about why this is intentionally “small”:

- It’s not meant to be a production-grade graph exporter.

- It’s meant to make the autograd machinery legible.

- It doesn’t need any external packages, which matters in Colab and teaching contexts.

The notebook then uses this visualizer on several expressions:

(x * 2).sum()(x * w + b).sum()((x + 1) ** 2).sum()- shared dependency

(a + a).sum() (x @ W).sum()

The pattern is consistent: build a tensor expression, call show_graph, and print the lines.

def show_graph(expr_name, y):

print('===', expr_name, '===')

for line in visualize_autograd_graph(y):

print(line)

x = torch.randn(5, requires_grad=True)

y1 = (x * 2).sum()

show_graph('y1 = (x * 2).sum()', y1)

The “shared dependency” example is especially instructive because it shows why the visited set exists:

x = torch.randn(5, requires_grad=True)

a = x * 2

y4 = (a + a).sum()

show_graph('y4 = (a + a).sum() [shared dep]', y4)

If you’ve ever tried to traverse a graph without a visited-set, you know what happens next.

Finally, the notebook includes edge cases:

requires_grad=Falseresults should report “no autograd graph.”max_depth=0should stop early (but still be informative).

t = torch.randn(3, requires_grad=False)

lines = visualize_autograd_graph(t)

assert 'grad_fn is None' in lines[0]

x = torch.randn(3, requires_grad=True)

y = (x * 2).sum()

short = visualize_autograd_graph(y, max_depth=0)

assert any('max_depth' in s for s in short) or len(short) > 0

This kind of assert-driven teaching is the point: it’s not just “here’s what I think will happen.” It’s “here’s what happens, and the notebook will enforce it.”

Appendix: The 10-minute checklist I wish I used earlier

If you want a practical way to apply this notebook to real projects, here’s the exact checklist I run when something feels off. It’s intentionally mechanical; the goal is to stop “vibes debugging.”

A) Make runs reproducible enough

Before I trust any debugging signal, I want runs to be stable. The notebook does the basic version of this:

import random

random.seed(0)

torch.manual_seed(0)

# Determinism can throw on some ops/platforms; keep it guarded.

try:

torch.use_deterministic_algorithms(True)

print('Deterministic algorithms: ON')

except Exception as e:

print('Deterministic algorithms: unavailable:', type(e).__name__, str(e)[:120])

I like this pattern because it’s honest: determinism is great when it works, but it’s not always available (and in some environments it can be slow). Guarding it means you don’t block the whole notebook on a platform-specific limitation.

B) Print shape_str on “boundary tensors”

I’m not printing everything—just the tensors that cross boundaries:

- model inputs and outputs

- anything that gets reshaped, permuted, squeezed, or unsqueezed

- anything that gets broadcast with a bias/weight

If a tensor crosses a boundary, it gets a shape_str(t) print. This is the same idea as logging at API boundaries in backend services.

C) Add expect_shape after every reshape/broadcast

The trick is to assert right after the operation that could be wrong. If you assert later, you force yourself to debug the downstream symptom instead of the upstream cause.

Example: if you want a (B, 1) bias, assert it:

bias = bias.unsqueeze(1)

expect_shape(bias, (batch, 1))

D) When gradients look haunted, ask three questions

The notebook’s “ghost gradients” section boils down to three fast questions:

- Did I call

backward()yet? (yes, it happens) - Is the tensor a leaf? If it isn’t,

.gradbeingNoneis normal. - Did I detach / enter

no_grad/ do an in-place op? These can legitimately break the graph or stop tracking.

If I’m still unsure, I print the autograd dependency tree starting from the result, because it answers the most important debugging question: “What operations are upstream of this value?”

The Insight

There are a lot of tools that promise to make deep learning easier: higher-level training loops, automatic mixed precision, distributed training frameworks, and increasingly smart debuggers.

And they’re genuinely useful.

But the stuff that wastes the most developer time hasn’t changed:

- tensors silently having the wrong shapes

- broadcasting doing valid-but-unintended math

- gradients being

Nonefor reasons that are correct but non-obvious

What’s funny (and slightly tragic) is that the fixes are not complicated. They’re just habits:

- Make your assumptions explicit.

- Assert shapes like you assert types.

- Prefer “broadcast on purpose” patterns (with

unsqueezeand comments). - Learn leaf vs non-leaf once, properly.

- When things still feel spooky, inspect

grad_fnand the dependency chain.

That’s also why I’m bullish on “teaching via verified notebooks.” The notebook format can be more than narrative—it can be executable truth.

What I learned (the blunt version)

- If you’re not asserting shapes, you’re accepting silent bugs as a lifestyle choice.

- Broadcasting is a power tool. Power tools are great until you forget which axis is which.

view()isn’t “worse” thanreshape()—it’s stricter. If it fails, it’s telling you something real..grad is Noneis usually not a disaster. It’s often just “this tensor is non-leaf.”- Building a tiny graph visualizer is easier than you think, and it pays off immediately in intuition.

Where this goes next

That's about basic graph intuition and a readable autograd dependency dump. In next chapter you'll turn that intuition into mechanics:

- gradient accumulation and

zero_grad detachvsno_grad- custom

torch.autograd.Function - gradient checking

But the foundation is the same: if you can predict shapes and interpret autograd metadata, the rest stops being magical.

And honestly? That’s the best outcome. Deep learning should feel like engineering, not seance.