Recently I wrote a neural network that trained beautifully.

By “trained beautifully,” I mean the loss didn’t move at all, the GPU fans were screaming, and my optimizer was faithfully stepping… absolutely nothing.

The funniest part is that the bug wasn’t in the math. It wasn’t in backprop. It wasn’t even in the optimizer. It was the most unsexy thing imaginable: my model didn’t know it had parameters.

PyTorch didn’t yell at me. It didn’t throw an exception. It just calmly let me waste time. Because when you’re not using nn.Module correctly, you’re basically writing a play where the actors never show up—and the stage manager (the optimizer) has nobody to pay.

So this post is about the “magic” of PyTorch that isn’t magic at all. It’s mostly bookkeeping. And once you understand the bookkeeping, you can build complex networks without losing your mind.

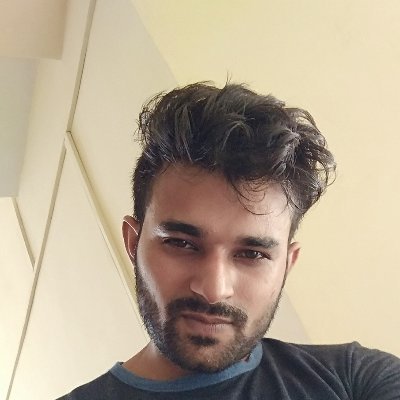

The Problems

As models get bigger, there are two kinds of problems:

- Math problems (vanishing gradients, bad initialization, wrong loss, exploding activations).

- Engineering problems (you forgot to include a layer in

.parameters(), you moved half the model to GPU, you saved the wrong state, you built an architecture that can’t be inspected).

The painful truth is that many beginner (and honestly, intermediate) PyTorch bugs are in category (2). You can write “correct” code that executes perfectly and still trains like a rock.

This tutorial is essentially an antidote: it shows how PyTorch’s nn.Module system turns your model into a trackable, movable, savable collection of parameters—as long as you play by the registration rules.

And yes, those rules are strict. That’s the point.

The Technical Deep-Dive

1) nn.Module: the boring infrastructure that makes big models possible

The notebook opens with the question:

How do we organize complex neural networks without losing our minds?

The answer: subclass nn.Module.

A raw-tensor approach collapses once you have dozens of layers. You need:

- a way to move everything to GPU (

model.to(device)) - a way to save/load weights reliably (

state_dict) - a way to hand parameters to the optimizer (

model.parameters()) - a way to switch training/eval behaviors consistently (

model.train()/model.eval())

All of those are not “deep learning concepts.” They’re state management.

Why not just use plain Python classes?

You can. But then you need to manually discover and manage everything you created. If you nest modules inside modules, and you forget to include one tensor… your model will silently degrade into an untrainable sculpture.

nn.Module solves this by maintaining registries:

- parameters: things wrapped in

nn.Parameter - submodules: things that are themselves

nn.Module - buffers: persistent non-parameter tensors (e.g., running stats in BatchNorm)

One mental model that helped me: an nn.Module is a tree of modules plus a catalog of state. If your weights aren’t in that catalog, they’re basically invisible to the training machinery.

A key phrase from the notebook:

nn.Modulehandles this state management automatically. It uses strict registration (via__setattr__) to track everynn.Parameterand sub-module you assign.

Translation: when you do self.something = ..., PyTorch intercepts the assignment and decides whether it should be tracked.

That strictness is why PyTorch can scale to absurd architectures without you writing a custom “walk the object graph and find tensors” function.

What nn.Module unlocks (the practical list)

Imagine you have 100 layers and you want to do three things:

- Move the whole model to GPU.

- Save all weights.

- Get learnable params for the optimizer.

Those are exactly the moments where a plain Python class becomes a liability. You can absolutely write:

class MyNet:

def __init__(self):

self.w = torch.randn(10, 10, requires_grad=True)

…and then manually keep track of device moves and serialization. But once you have nesting and multiple layers, “manual” turns into “I will forget one thing and spend three hours debugging why training is frozen.”

nn.Module centralizes that state. Then you get:

model.to(device)to move registered parameters/modulesmodel.state_dict()as a reproducible snapshot of registered statemodel.parameters()andmodel.named_parameters()to drive optimizersmodel.train()/model.eval()to toggle behavior for layers like Dropout

Your first debugging tool: print the model

You saw it in the notebook when printing nn.Sequential and a custom ModuleList model. Printing a module gives you a structural overview. It’s not a full graph trace, but it’s a fast sanity check.

seq_model = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(10, 20),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(20, 5)

)

print(seq_model)

If your model printout doesn’t contain the layer you thought you added, your training won’t contain it either.

2) nn.Parameter: the wrapper that decides whether your optimizer has a job

The notebook nails the beginner trap with a painfully relatable snippet:

class BadLayer(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.weights = torch.randn(10, 10, requires_grad=True) # <--- WRONG

This looks reasonable. It’s a tensor. It has requires_grad=True. Surely PyTorch will update it.

Here’s the kicker: the optimizer won’t see it, because it isn’t registered as a parameter.

In PyTorch, “learnable weight” means “an instance of nn.Parameter assigned as an attribute of an nn.Module.” That wrapper is the contract.

The notebook’s demo makes it explicit:

class DemoModule(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.my_tensor = torch.randn(3, requires_grad=True) # Regular tensor

self.my_param = nn.Parameter(torch.randn(3)) # Parameter

demo = DemoModule()

print("Parameters found by .parameters():")

for name, param in demo.named_parameters():

print(f" - {name}: {param.shape}")

Only my_param shows up.

The silent optimizer demo

Here’s a tiny pattern that captures the failure mode (this is the same concept as the notebook’s “Invisible Tensor,” just shown as a training step):

class BadLayer(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

# Looks learnable, but not registered.

self.weights = torch.randn(10, 10, requires_grad=True)

layer = BadLayer()

print(list(layer.named_parameters())) # empty

Now imagine you did something like:

opt = torch.optim.SGD(layer.parameters(), lr=0.1)

layer.parameters() is empty, so the optimizer gets an empty parameter list. No exception. No warning. It will happily run and “step” nothing.

This is why I’ve learned to treat list(model.named_parameters()) like a pre-flight checklist item. If it’s empty when you expect it not to be, stop everything.

“But requires_grad=True should be enough!”

It’s enough for autograd to compute gradients. But optimizers don’t rummage through your Python object looking for any tensor with grad.

Optimizers consume an explicit list of parameters. That list comes from model.parameters() and model.named_parameters(). Those methods return what the module has registered.

So the failure mode is subtle:

- autograd computes gradients for your tensor

- but your optimizer never steps it

- training looks like it “runs” but doesn’t learn

This is the kind of bug that makes you question your entire career.

Registration is also why saving/loading works

When you call model.state_dict(), PyTorch returns a mapping of parameter names to tensors. Those names come from the registration tree. If you store your “weights” in an unregistered attribute, they won’t show up in state_dict(). Which means:

- You can train something and accidentally save a checkpoint missing key tensors.

- You reload later and the model “loads” but doesn’t behave like the trained version.

That’s another silent failure mode. Again: boring bookkeeping, huge consequences.

__init__ vs forward: where things belong

The notebook’s distinction is worth repeating because it’s a pattern you’ll use forever:

__init__: define layers and parameters (run once)forward: define how data flows (run every call)

Even if you can create tensors in forward, doing so usually means they won’t be registered parameters (and they’ll get recreated every pass).

3) Containers: Sequential vs ModuleList vs “a plain list

At some point you’ll want a variable number of layers. The obvious Python move is:

self.layers = [nn.Linear(10, 10), nn.Linear(10, 10)]

And the notebook bluntly warns you: this will fail silently.

Why? Because a plain Python list is invisible to the registration system. PyTorch won’t traverse arbitrary containers and register modules inside them.

So:

model.to('cuda')won’t move those layersmodel.parameters()won’t return them- the optimizer won’t update them

You get a model-shaped object that behaves like a model during forward… but not during training.

A concrete “plain list” pitfall

If you’ve never been bitten by this, congrats—you will be (yes, it’s as strange as it sounds). Consider:

class BadListNet(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.layers = [nn.Linear(10, 20), nn.Linear(20, 5)] # plain Python list

def forward(self, x):

x = self.layers[0](x)

x = torch.relu(x)

return self.layers[1](x)

Forward works. But:

model = BadListNet()

print(len(list(model.parameters()))) # often 0

The fix is exactly what the notebook teaches: nn.ModuleList.

nn.ModuleList: a list that PyTorch can see

Use nn.ModuleList when:

- you want to hold a list of submodules

- you want to index them or loop them

- you want full PyTorch registration behavior

The notebook’s example:

class MyListModel(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.layers = nn.ModuleList([

nn.Linear(10, 20),

nn.Linear(20, 5)

])

def forward(self, x):

x = self.layers[0](x)

x = torch.relu(x)

x = self.layers[1](x)

return x

Notice the tradeoff: you gain flexibility, but you must write forward explicitly.

There’s a subtle upside here too: because you control forward, it becomes much easier to print intermediate activations and debug shapes. In practice, that’s the difference between “I have a model” and “I can actually maintain this model.”

nn.Sequential: great until you need to look inside

nn.Sequential is ideal for linear stacks where the output of one layer feeds directly into the next.

Pros:

- concise

- simple

Cons:

- intermediate values are hidden

- non-linear topologies (skip connections, multiple inputs, branching) don’t fit

The notebook’s table summary is basically correct: Sequential is rigid but quick; custom modules are flexible and debuggable.

My personal rule:

- Use

Sequentialfor small blocks (Conv → ReLU → Pool style). - Use custom

nn.Modulewhen you care about inspecting or branching.

One more practical note: if you do want to debug inside a sequential block, you can break it into named submodules or temporarily replace it with a custom module that prints intermediate shapes. Debuggability is a design choice.

4) Implementing a Linear layer from scratch: the contract is parameters + math

This part of the notebook is where you stop treating nn.Linear as an oracle.

A Linear layer is:

y=xWT+b

And the notebook highlights why the transpose exists:

- input

xshape is(batch, in_features) - weight

Wis stored as(out_features, in_features) - to compute

(batch, out_features)you dox @ W.T

The MyLinear exercise skeleton

The notebook provides a scaffold (with TODOs), which is nice because it forces you to implement the two essential responsibilities of a layer:

- register parameters (

weight,bias) usingnn.Parameter - implement

forwardwith the correct matrix math

Here’s the scaffold excerpt:

class MyLinear(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, in_features, out_features, bias=True):

super().__init__()

self.in_features = in_features

self.out_features = out_features

# TODO: Create the weight parameter

# Shape should be (out_features, in_features)

# self.weight = nn.Parameter(...)

if bias:

# TODO: Create the bias parameter

# Shape should be (out_features)

# self.bias = ...

pass

else:

self.register_parameter('bias', None)

self.reset_parameters()

def forward(self, input):

# TODO: Implement y = x @ W.T + b

raise NotImplementedError("Implement forward pass")

And it includes a verification cell that compares to nn.Linear by copying weights and checking output:

with torch.no_grad():

my_layer.weight.copy_(torch_layer.weight)

if my_layer.bias is not None:

my_layer.bias.copy_(torch_layer.bias)

x = torch.randn(4, in_f)

my_out = my_layer(x)

torch_out = torch_layer(x)

diff = (my_out - torch_out).abs().max().item()

That verification pattern is a great habit: match a reference implementation by synchronizing weights, then compare outputs.

A “before/after” that actually matters

Before you implement MyLinear, your verification cell prints something like:

TODO: Implementation incomplete

After you implement it correctly, the verification cell should produce:

PASS: Output matches nn.Linear

This is exactly the kind of small, local correctness check that prevents you from debugging training dynamics when the underlying layer is wrong.

Also: once you implement MyLinear, you’ll notice that parameter registration is automatic—as long as you used nn.Parameter. The verification cell explicitly checks:

if not isinstance(my_layer.weight, nn.Parameter):

print("FAIL: weight is not an nn.Parameter")

Again: the notebook is basically teaching you to debug state registration, not just math.

Why initialization exists (and why you shouldn’t ignore it)

The notebook uses Kaiming uniform initialization:

nn.init.kaiming_uniform_(self.weight, a=np.sqrt(5))

This matters because raw random initialization can explode or vanish gradients. You don’t have to memorize the derivations to appreciate the practical outcome:

- good init means training starts in a numerically sane region

- bad init means you spend time debugging optimizers when the issue is the starting weights

Even for toy layers, it’s worth using a standard initialization.

5) Turning math into Lego: Activations as nn.Modules

The notebook’s activation section starts with a question that sounds silly until you’ve tried it:

Why wrap simple math functions (like ReLU) in classes?

Because nn.Sequential only accepts nn.Module objects.

Yes, you can write x = x * (x > 0) in a custom forward, but you can’t drop that into a Sequential container. So if you want composable building blocks, you wrap your activation as a module.

The notebook provides exercise stubs:

class MyReLU(nn.Module):

def forward(self, x):

# Hint: torch.maximum or x * (x > 0)

return x # Placeholder

class MySigmoid(nn.Module):

def forward(self, x):

# Hint: torch.exp(-x)

return x # Placeholder

class MyTanh(nn.Module):

def forward(self, x):

return x # Placeholder

And it includes verification checks comparing to torch.relu, torch.sigmoid, and torch.tanh.

This is a small lesson with a big payoff: PyTorch is designed around modules as composable units. If you want to build architectures like Lego, you need every piece to be a module.

And once you do that, you unlock patterns like:

mlp = nn.Sequential(

MyLinear(10, 20),

MyReLU(),

MyLinear(20, 5)

)

That’s the “Lego” moment: your own layers and activations can plug into the same containers as PyTorch’s built-ins.

6) Dropout: randomness, training mode, and “inverted scaling”

Dropout is one of those features that seems like a prank until you understand the intention:

Why would we randomly delete neurons?

Because it reduces co-adaptation and discourages memorization. It forces redundancy and robustness.

The notebook’s sports-team metaphor is good: training with random players missing prevents the team from relying on one superstar.

The key implementation detail: inverted dropout

If you zero out activations with probability p, your expected activation magnitude drops. If you do nothing, the next layer sees a smaller signal during training than during inference.

“Inverted dropout” fixes this by scaling the kept activations by 11−p during training, so the expected value stays consistent.

The notebook’s MyDropout skeleton emphasizes three steps:

- check

self.training - if training: sample mask and scale

- if eval: return identity

And the verification cell checks:

- output changes in training mode

- roughly p fraction zeros

- non-zeros are scaled to 11−p

- eval mode returns input unchanged

This is an important engineering insight: PyTorch layers often behave differently in train vs eval. That behavior is standardized through:

model.train()model.eval()

Dropout is the canonical example. BatchNorm is the other.

Train/eval is a recursive switch

One reason nn.Module matters is that mode changes propagate through the entire module tree:

model.train() # sets self.training=True for all submodules

model.eval() # sets self.training=False for all submodules

That’s why the notebook tells you to check self.training inside MyDropout.forward. You don’t need a separate flag; you inherit the model-wide mode.

This is also why manually managing layers without nn.Module becomes painful: you’d have to propagate “training vs eval” yourself.

The Insight

If you zoom out, This is basically teaching one idea:

PyTorch isn’t just tensors and gradients. It’s a framework for stateful, composable computation blocks.

nn.Module is the foundation:

- it’s how parameters become discoverable

- it’s how devices are handled consistently

- it’s how training/eval modes propagate through the whole model

- it’s how saving/loading becomes reliable

The “magic” is mostly registration and bookkeeping. Which sounds boring—until you build a 50-layer model and realize boring is what you want.

One last industry-context thought: modern PyTorch features like tracing (FX) and compilation (torch.compile) increasingly rely on models being well-structured modules. Clean module graphs are easier to transform, optimize, and debug. So the “building blocks” lesson here isn’t just pedagogy—it’s future-proofing.

Practical takeaways I’d actually tape to my monitor

- If

model.parameters()is empty, you almost certainly forgotnn.Parameteror forgot to subclassnn.Moduleproperly. - If you put layers in a plain list, you built a silent failure. Use

nn.ModuleList. nn.Sequentialis great for simple stacks, but customforwardis where debugging becomes sane.- For custom layers, verify against PyTorch’s reference (

nn.Linear,F.linear,torch.relu, etc.) by copying weights and comparing outputs. - Train/eval mode isn’t a vibe; it’s a switch that changes behavior (Dropout is the proof).

And my personal “if something feels off” checklist:

- Run

sum(p.numel() for p in model.parameters())and sanity-check the magnitude. - Print

next(model.parameters()).deviceafterto(device)to confirm movement. - Confirm your containers are

ModuleList/Sequential, not plain Python lists.

What might improve in the future?

A lot of modern tooling (TorchScript, torch.compile, FX tracing) tries to make models more analyzable and optimizable. But even as PyTorch becomes more compiler-driven, the core ergonomics will still depend on module structure.

Because the real enemy isn’t a lack of performance.

It’s the silent bugs.

And PyTorch’s strict “only registered things matter” rule is one of the best silent-bug preventers we have—once you know how to work with it.

Appendix: A tiny checklist (the stuff that prevents pain)

- Print your model and scan for missing layers.

- Run

list(model.named_parameters())before training. - Verify

.to(device)moves everything (especially when using containers). - Confirm

model.train()before training andmodel.eval()for eval/inference. - When implementing

MyLinear/activations/dropout, validate against PyTorch’s reference outputs.